How a Better Bile Acid Could Keep C. diff at Bay

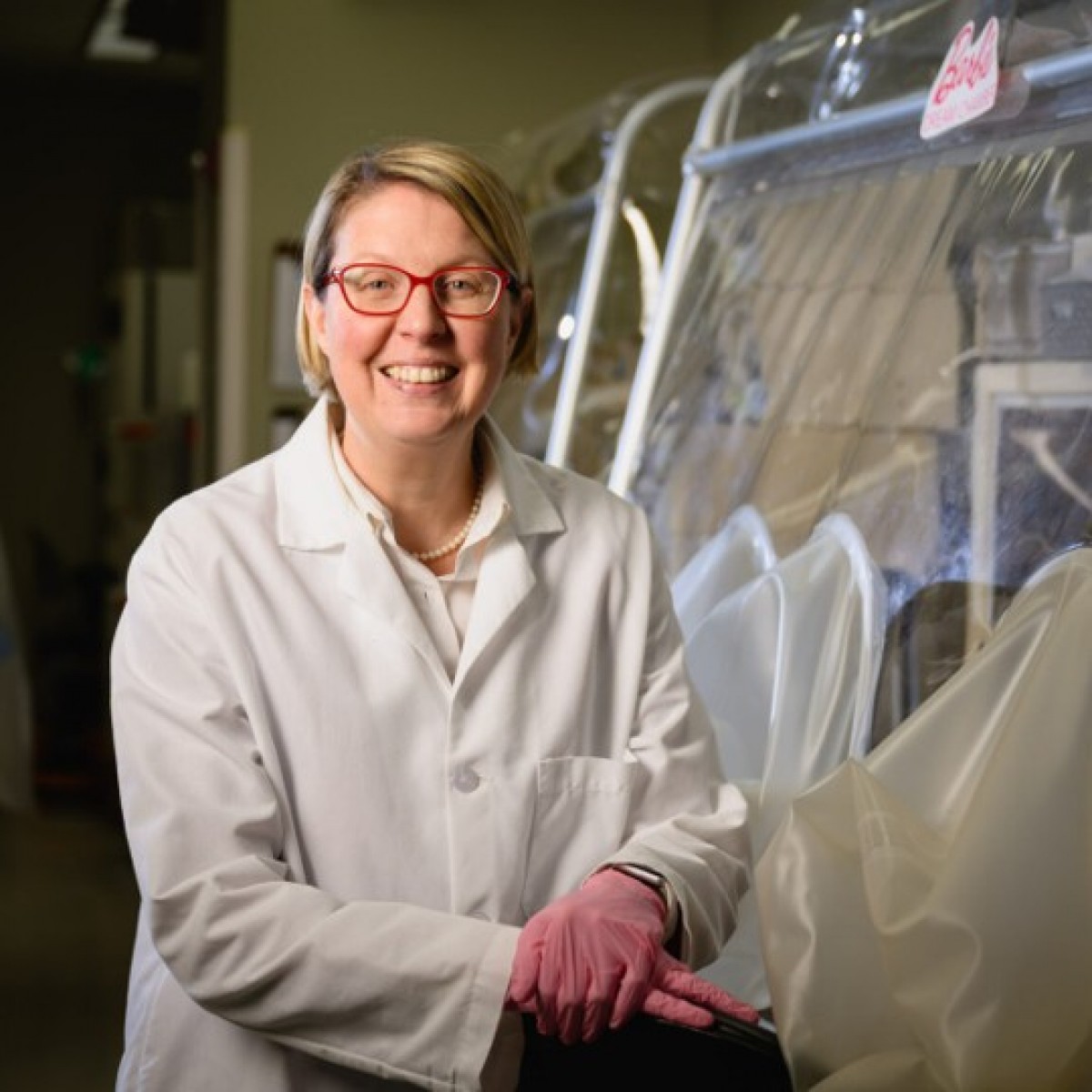

Once a C. diff infection takes hold in a person's body, the bacteria is challenging to dislodge. NC State microbiologist Casey Theriot and her colleagues think adding engineered bile acids to the gut could stop C. diff bacteria from re-populating after treatment.

One of the worst things about a Clostridioides difficile infection is how often it comes back. Frequently, a patient will be treated with the antibiotic vancomycin, and the terrible intestinal symptoms will disappear, only to flare up when treatment ends.

A C. diff infection is more than simple diarrhea. Every year in the United States, 500,000 people will suffer from C. diff infections, often acquired in a medical setting or after antibiotic treatment. Of those, 30,000 will die.

Part of the reason the infection returns is because the ecosystem of the gut becomes disrupted by antibiotic treatment. Like a wildfire roaring through the gut, antibiotics may kill off C. diff, but they kill friendly bacteria, too. Without normal gut bacteria, balances of bile acids become disrupted. It’s all too easy for C. diff to step back in the burned gut landscape – a weed sprouting up before the forest can return.

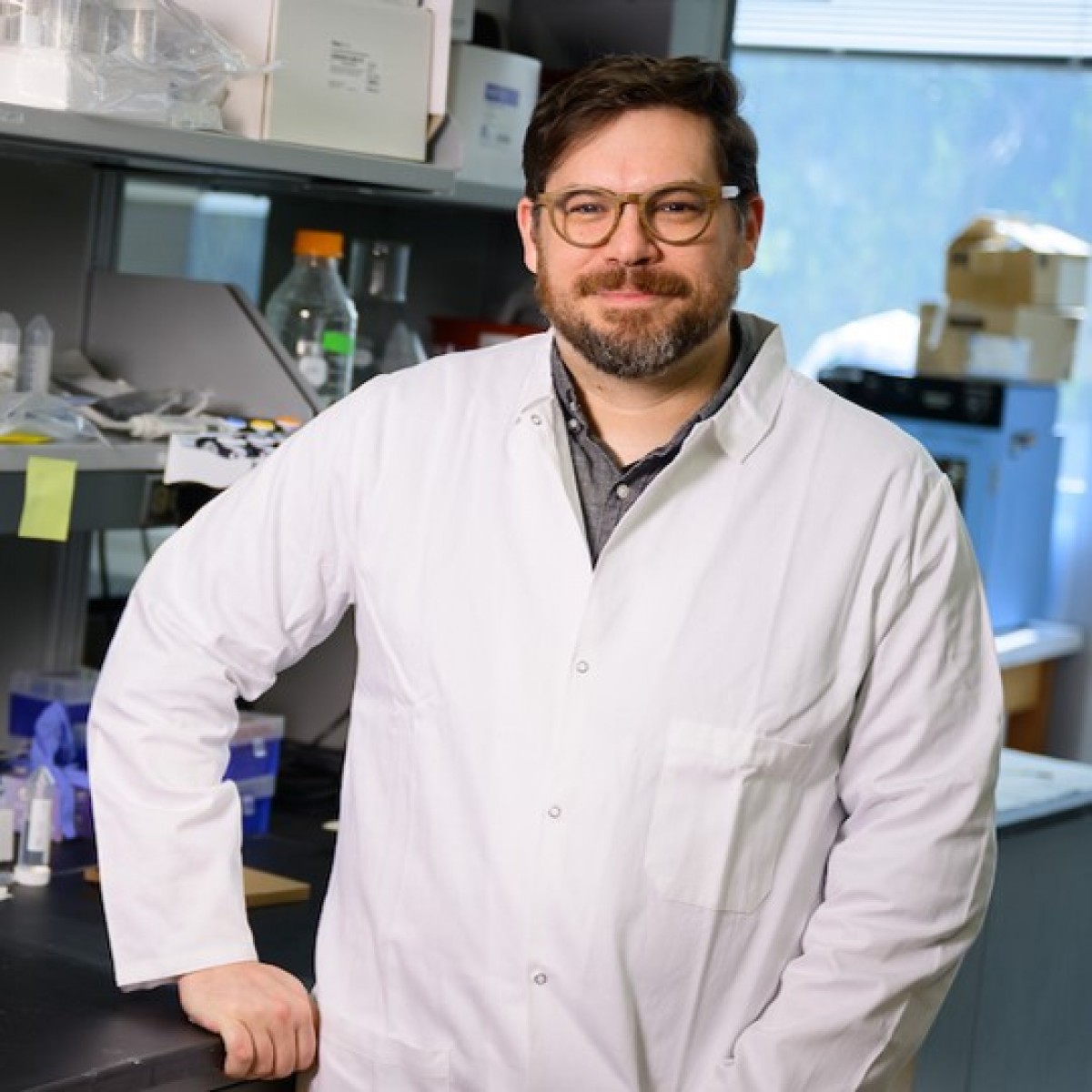

Casey Theriot, a microbiologist and infectious disease expert at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, is working on new ways to prevent C. diff from coming back. Working with biochemist Roman Melnyk at the University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Children, Theriot and her colleagues have shown that a synthetic bile acid might do the trick. In the patient’s gut, the new bile acid could help prevent the C. diff toxin from causing damage to the colon by binding to its cells, and allowing normal gut bacteria much-needed time to grow back.

Bile acids help break down food, but making them requires bacteria. Primary bile acids are made in the liver, derived from cholesterol.

“Primary bile acids, as they make their way down the small and large intestine, are further converted to other bile acids that we most of the time call secondary bile acids by members of the gut microbiota,” Theriot explains.

These secondary bile acids in particular have an extra role to play. “The interesting thing is that many of these secondary bile acids are very important for warding off enteric pathogens,” Theriot explains. The bile acids can take thousands of forms, she says. “My lab is very specifically focused on understanding certain subsets of these and how bacteria make them, how that affects C. diff and the host response in the colon.”

The symbiotic relationship between host-produced bile acids and gut bacteria could play an important role in human health. “Alterations in [bile acid balance] are associated with inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome and colon cancer” she notes. “We’re finding that if you can control the bile acid pool in the body, you might be able to prevent a lot of diseases.”

A good bile acid balance could help prevent C. diff from colonizing the gut. The pathogen uses primary bile acids as a signal to proliferate, so a better balance of primary and secondary bile acids might stop the signal and keep the infection from taking hold, Theriot says. Some secondary bile acids also prevent C. diff from proliferating, and could be used to prevent the infection.

C. diff produces toxins as part of its infection, and one of them, TcdB, is a major cause of C. diff symptoms. It burrows into intestinal cells and changes the cell structure The cell becomes leaky and loses fluid — helping to cause the symptoms of C. diff infection. Inhibiting TcdB can stop C. diff gaining access to intestinal cells and preventing inflammation.

It turns out that a synthetic secondary bile acid might be up to that job. To get into a cell, TcdB has to open, a bit like a door on a hinge. By studying the shape of TcdB and comparing it against different bile acids, Theriot and her colleagues showed that some secondary bile acids could clamp onto the “hinge” of TcdB, preventing it from opening and gaining entry into the cell.

Using these bile acid structures, the researchers designed three synthetic bile acids and tested them against TcdB. They also faced an additional challenge — getting the drug to the intestine where C. diff infection takes hold. Most people want to swallow their medications, requiring the bile acid to make it to the colon where C. diff thrives.

But bile acids don’t make it past the small intestine. Normally, “95 percent of the bile acids are shuttled back through enterohepatic recirculation, and they go back into the bloodstream, to all different organs in the body, but especially back to the liver, and they get recycled,” Theriot explains. If the bile acids can’t get to the colon, they can’t tackle C. diff there.

Of the synthetic bile acids the team developed, only one was tested, sBA-2, made it to the colon in large amounts. Theriot tested it in her mouse model of C. diff prevention — a model used around the world as scientists work to develop treatments for the infection. The mice who got sBA-2 were protected against disease compared to controls and also has less C. diff bacteria in their systems. Theriot and her colleagues published their findings Nov. 18 in Nature Microbiology.

Unfortunately, there’s no telling when someone will get infected with C. diff for the first time. Some people might be exposed to C. diff for the first time in a medical setting. The tough bacterium can linger on surfaces, on unwashed hands or in food or water, ready to be swallowed. But like a weed in a lawn, a few people have it naturally in their guts – restrained to low levels possibly by bile acid balance and normal gut bacteria.

“I don’t think this is going to be a prophylaxis,” Theriot says. Rather, she sees sBA-2 as a therapy that could be used to keep C. diff from recurring after treatment with vancomycin.

After the antibiotics, she explains, “You still have an altered microbiota” so sBA-2 could be used to prevent C. diff from gaining another hold and proliferating, allowing someone’s regular bacteria the time it needs to regrow. “Then you’ll be over the hump of that susceptibility window.”

Bile acids like sBA-2 are part of Theriot’s effort to get beyond treating C. diff with antibiotics that wipe out all the gut bacteria. “We really need to get something more targeted,” she says.

“The reason I keep focusing on C. diff, and I probably will for a long time, is these people are dying,” Theriot says. A synthetic bile acid couldn’t just help stop infections — it also could save lives.

Author: Bethany Brookshire

Source: https://news.cvm.ncsu.edu/

List

Add

Please enter a comment