Free-Roaming Cats Drive Toxoplasmosis Spread

Free-roaming cat population estimates in the United States range from 10 million to 114 million cats, and pet owners whose cats spend time outdoors contribute to these numbers. Advocates for letting cats outside cite benefits such as the cat being more physically active, which keeps them at a healthier weight, and increased environmental enrichment, including using their natural hunting skills. Critics say the practice threatens biodiversity, because the cats eat birds, reptiles, small mammals, and important insects such as butterflies and dragonflies. In addition, a University of British Columbia (UBC) study suggests free-roaming cats play a significant role in spreading toxoplasmosis to wildlife, especially in densely populated urban areas.

Toxoplasmosis in cats

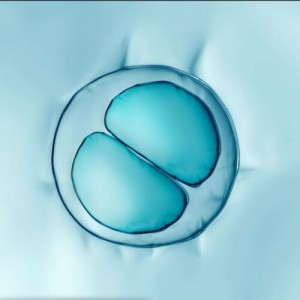

Toxoplasmosis is caused by the single celled microscopic parasitic organism Toxoplasma gondii, which can infect virtually any warm blooded animal. The cat is the natural host, however, meaning the organism can complete their life cycle while parasitizing the cat. When a cat eats infected prey or contaminated meat, encysted parasites are released that enter the cat’s digestive tract, reproduce, and produce oocysts. The cat begins shedding these oocysts in their feces about 3 to 10 days after infection, and can continue shedding for about 10 to 14 days. One infected cat can excrete up to 500 million T. gondii oocysts in this time frame, and the parasites can survive for years in soil and water, potentially infecting other animals, including humans. Infected cats typically show signs only when their immune system is suppressed, making detection difficult, but if they do, they may exhibit fever, lethargy, decreased appetite, difficulty breathing, uveitis, and neurological signs.

Toxoplasmosis in humans

Most human toxoplasmosis infections are caused by consumption of undercooked, contaminated meat, and exposure to infected cat feces. In utero transmission can also occur, putting pregnant women and immunocompromised people at highest infection risk. Most healthy people have no symptoms or only flu-like signs, including body aches, swollen lymph nodes, headache, fever, and fatigue. Immunocompromised people are at risk for more severe symptoms, such as pneumonia, seizures, and retinopathies. Infants born infected are at risk for seizures, liver disease, and severe eye infections. The disease has also been linked to nervous system disorders, certain cancers, and other debilitating chronic conditions.

Toxoplasmosis in wildlife

When a wild animal ingests a sporulated oocyst in their environment, infection causes cysts in various body tissues that remain throughout the animal’s life, and can cause infection if other animals or people eat cyst-containing tissue. Infectious parasites may also be secreted in an infected cow or goat’s milk. Toxoplasmosis can cause significant illness and increase mortality and morbidity rates in wild animals, but infection can also cause problems for animals not severely affected. Subtle issues, such as changes in anti-predator behaviors, reduced breeding success, and decreased competitive fitness, can place these animals at greater risk for threatening processes.

The UBC study researchers used data from 202 global studies to examine 45,079 toxoplasmosis cases in wild mammals, and found that wildlife living near dense urban areas were more likely to be infected. This suggests that free-roaming domestic cats are the most likely cause of these infections, because as human densities increase, domestic cat populations grow, and wild felid numbers decrease. These findings also indicate that T. gondii’s impact on wildlife can be reduced by limiting free-roaming cats. The study also demonstrated that healthy ecosystems protect against T. gondii—for example, ecosystems that can sustain native predator populations can prevent domestic cats from entering important wildlife areas, and lead to lower environmental pathogen deposits. In addition, vegetated landscapes that have healthy soil bacteria and invertebrates can filter out or inactivate the pathogen.

The veterinarian’s role

Veterinarians can help mitigate this problem by addressing the issue with their clients. They can persuade pet owners to keep their cats indoors with several facts, including:

- The cat’s welfare — Indoor cats have an average lifespan 5 to 10 years longer than an outdoor cat. Outdoor cats are more likely to be hit by a car, attacked by another animal, or ingest a toxic substance, and are at increased risk for diseases transmitted by fleas, ticks, and mosquitoes.

- The owner’s pocket book — Treating medical conditions that result from being outdoors can be expensive, and the owner’s money is much better spent on wellness and preventive care.

- Wildlife conservation — Cats kill an estimated 12.3 billion wild mammals and 2.4 billion birds annually in the United States, which contributes to biodiversity loss in the environment.

- Public health risks — In addition to toxoplasmosis, cats can spread other zoonotic diseases, such as rabies, cat scratch fever, ringworm, cryptosporidiosis, and giardiasis.

Decreasing the free-roaming cat population will help decrease the toxoplasmosis spread through wildlife, and will help cats live longer healthier lives. If your clients are concerned about enrichment in their cat’s life, offer advice on keeping their indoor cat happy and entertained with interactive cat toys and puzzle feeders. They can also consider installing an outdoor cat enclosure or teaching their cat to walk on a leash.

About the author:

Jenny Alonge received her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from Mississippi State University in 2002. She then went to Louisiana State University where she completed an internship in equine medicine and surgery. After her internship, she joined an equine ambulatory service in northern Virginia where she practiced for almost 17 years. In 2020, Jenny decided to make a career change in favor of more creative pursuits and accepted a job as a veterinary copywriter for Rumpus Writing and Editing in April 2021. She adopted two unruly kittens, Olive and Pops, in February 2022.

List

Add

Please enter a comment